During election campaigns, a large number of opinion polls is published by different companies. The basic idea of the Irish Polling Indicator is to take all available polling information together to arrive at the best estimate of current support for parties.

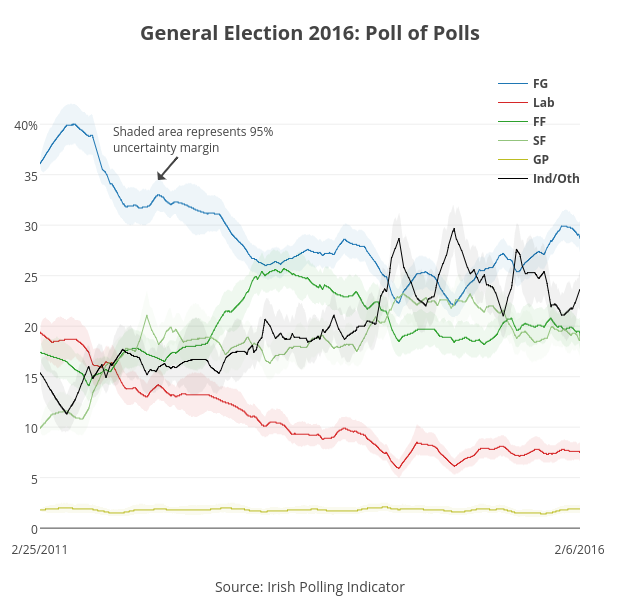

Currently, the Irish Poling Indicator estimates Fine Gael support at 29 per cent. The Taoiseach's party has gained support over the last year, after a low of 22 per cent in December 2014. The party is currently clearly in the lead, although it is down 7 per cent compared with the 2011 general election. Fianna Fáil is estimated at 20 per cent, which is marginally higher than its 2011 result.

For Sinn Féin, the current showing of 19 per cent represents a big improvement to its 2011 result.

While both parties are at a considerable distance from Fine Gael, it is not unthinkable that one of them might catch up with Fine Gael.

Labour, meanwhile, would be the main loser if current polls were reflected in the election result. At 8 per cent, it would be a poor election showing, not only compared to 2011 but also historically.

The Green Party seems unable to regain the support it lost in the 2011 election and has lingered around 2 per cent support for most of the current parliamentary term.

A broad grouping of Independents and Others is at 23 per cent support. This includes AAA-PBP at just over 3 per cent and newcomers Renua at about 1 per cent and the Social Democrats at just under 3 per cent.

The largest grouping within this block consists, however, of Independents (including the Independent Alliance) at almost 14 per cent.

For all of these figures, we must take into account a margin of error of about +/- 1.5 per cent for the larger parties and just under 1 per cent for the smaller ones.

House effects

Polls are great tools for measuring public opinion, but because only a limited sample is surveyed, we need to take into account sampling error. By combining multiple polls, we can reduce this error.

There are also structural differences between the polls of different pollsters. These are a result of the methodological choices they make: face-to-face or phone polls, quota sampling, weighting the data based on likelihood to vote or not.

With so many polls going around it is difficult to get a random sample of voters to participate in any one public opinion survey. Survey participants might not be fully representative for the whole electorate.

Pollsters use different adjustments to tackle these problems. However, this leads to structural differences between the results of different polling companies, so-called ‘house effects’.

For example, over the past Dáil, pollster Red C Research has consistently estimated Labour about 1 percentage point higher than the average pollster.

But how do you average two polls if one is conducted today, another one week ago and yet another one 3 weeks old? Just take the average of the three? Weight the more recent ones more heavily perhaps, but by how much exactly?

The Polling Indicator assumes that public opinion changes every day, but only by so much. If Labour was on 10 per cent last week and turns out to poll 18 per cent today, we might question whether one of these polls (or even both) are outliers, which just by chance contains many more or less Labour voters than there are in the general public.

The Polling Indicator assumes that support for a party can go up or down, but that radical changes are quite rare. But if one party is generally more volatile, it will take this into account.

Model

The Irish Polling Indicator uses a sophisticated statistical model to take all of this into account. In practice it means that more recent polls are weighted most heavily in the polling average. Polls with more respondents also feature more prominently, because their random error is smaller. And polls that are radically different from other recent polls are taken with a grain of salt.

The Irish Polling Indicator contains a rather large category of ‘Others/independents’, which lumps together minor parties and independent candidates. It is somewhat complicated to break this down in the context of the Irish Polling Indicator’s model, as these groups have not been consistently reported in polls over the entire parliamentary term.

As a way around this, support for these groups is analysed on a group-by-group basis. Basically, these analyses take into account all of the things the main model also looks at, but it does not guarantee that the support for these parties adds up exactly to the total for ‘Others/independents’.

In practice this is not too important. The breakdown includes three parties (AAA-PBP, Renua and Social Democrats) and Independent candidates/Independent Alliance, so there will be other even smaller parties that are not included in the breakdown.

Therefore the total of Other/Independents is likely to be higher than the sum of the four groups in the breakdown.

Predictions

Does this mean that the Irish Poling Indicator will perfectly predict the outcome of the general election?

No. First of all, polls represent current voting intentions; these might change over the election campaign.

Second, while random error is reduced by combining a lot of information, we should take uncertainty margins into account. Therefore we report these consistently.

Third, in dealing with pollsters’ “house effects” we assume that the average pollster is right. If all pollsters underestimate a party, so will our polling “average”.

If we apply this method to previous elections, we find that it does well for most parties, especially in the 2011 general election. The final Polling Indicator for 2011 deviates by an average of 0.73 per cent from each party's election result.

Tom Louwerse is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Leiden University, the Netherlands. He started his work on the Irish Polling Indicator when he held the same position at Trinity College, Dublin, between 2013 and 2015.